But so will any creative exploits you might have for fun, on the side.

In the wake of the recent U.S. general election, I was party to a conversation in which one of my friends, who works as an editor for a B2B publication, imagined a not-to-distant future in which editorial staff could be completely done away with.

Just point some AI at some sources of relevant data and information having to do with a particular sector, create some parameters around voice, style and such, and the AI does its thing. To some, it might sound farfetched, but from what we know of content farms and fake news sites, much of the process of churning out countless bits of content designed to drive consumption - including catchy (and often misleading) headlines - is somewhat automated already.

There's another bit that made me feel like content creation isn't all that far from the days where it runs on autopilot with an editor keeping a watchful eye and making adjustments.

Recently, I upgraded my digital audio workstation to Logic Pro X. This was an inevitable step on a path I started a long time ago, toward getting some of the musical ideas out of my head and turning them into actual songs.

With the upgrade came a bunch of cool new features, like you'd expect in a major upgrade of any type of software. One particular feature, though, hit me like a ton of bricks.

You can virtually simulate a drummer. No, I'm not talking about patching in the sound from some old drum machine and running repetitive loops to provide percussion over a song idea. I'm talking about actually simulating a drummer - that oft-maligned member of the band who seemingly everybody likes to bust on.

Logic Pro X lets you pick who should play drums on your song. The virtual drummers have names, not to mention styles, influences, and particular drum kits that they like. The kits are all impeccably sampled, piece by piece, from actual drum kits. The drummer I have in the song I'm currently working on is named Logan. He's more of a classic rock guy, sort of heavy-sounding, kind of in the vein of a Keith Moon or a John Bonham.

The thing about Logan is that he's completely obedient. He always shows up for band practice, and I can control everything about how he plays. The best part about Logan is that he doesn't sound robotic - I can control how far back he hangs on the beat, whether he rushes the band at any point, how likely he is to play fills, whether he's playing the high-hat or the ride cymbal during a particular passage. I can tell Logan that I hate his kit, and I can change it around, or swap in tom-toms from a completely different kit if I don't like the way he sounds. I can even make him make mistakes. If Logan pisses me off, I can fire him in the middle of a song if I feel like it, keep his recorded drum parts, and swap in another drummer.

Logan's big selling point, though, is that he sounds like a human. To the casual listener, he sounds like some guy I hired for a recording session.

I've never been able to play the drums. And now that we've automated the drummer, I'll never be left waiting for a drummer who blew off band practice, or have to argue with one who keeps rushing through the bridge.

This leaves me time to concentrate on other things, like arranging, playing guitar and piano parts, maybe doing some singing.

Speaking of which, my guitar skills have really deteriorated, and there's this song I can hear in my head. I spent an hour the other day trying to play the main riff and I just couldn't get it - there's one part where the string-skipping pattern is different from the rest of the riff, and I always blow it.

After an hour, I landed on a conundrum. I could spend the next hour or two trying to nail the riff perfectly, or I could play it once the wrong way, edit the hell out of it so that it sounded like I was playing it the right way, and move on. Guess which one I opted for.

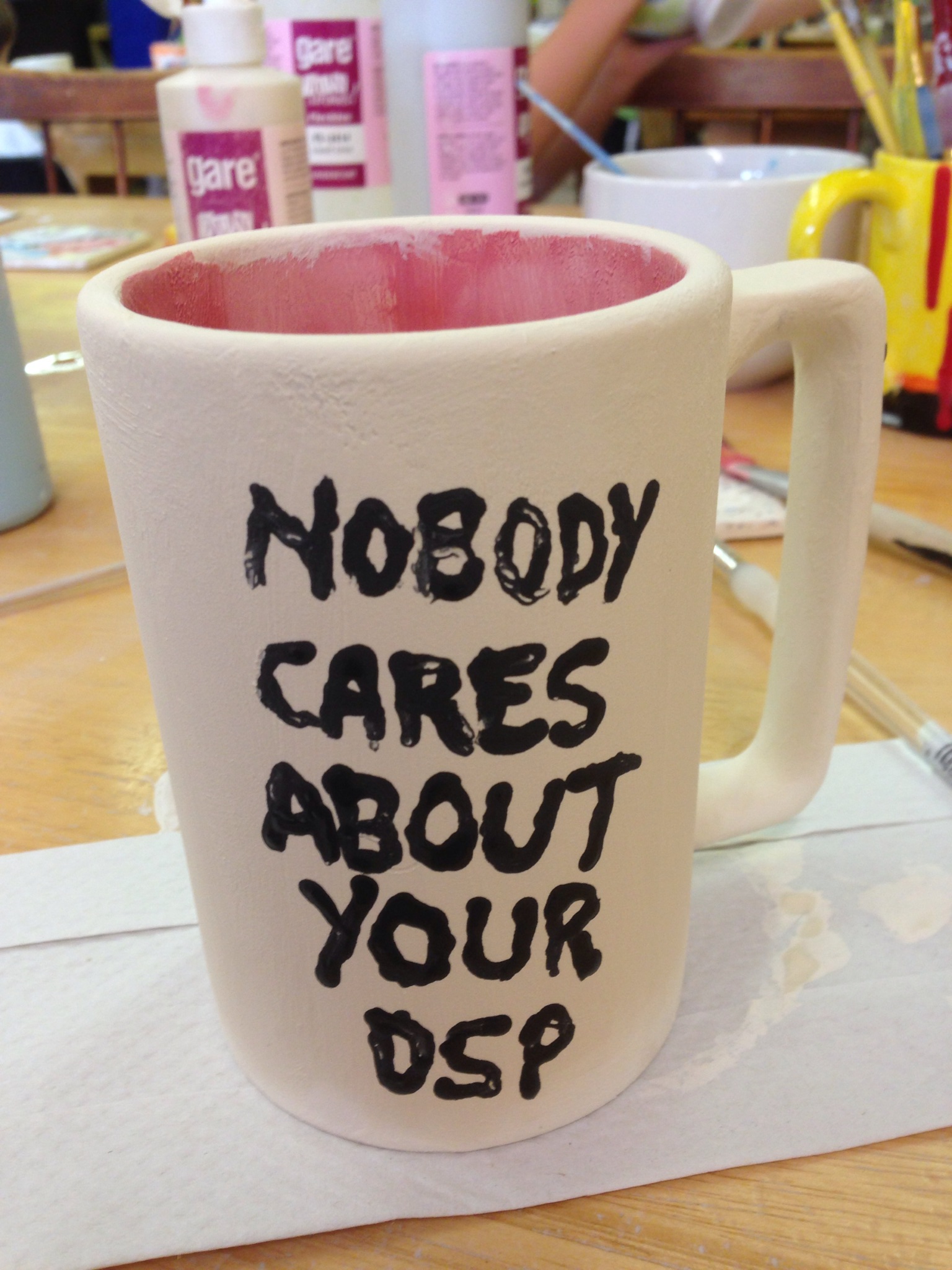

Whenever I've used recording software over the years, I've been able to justify that songs I wrote with it were entirely my own creation, because at least I could play all the parts. Now I'm not playing the drums (which is probably a good thing), and I'm fixing my guitar parts that are too complex for me to play without a lot more practice. Is the song really my own anymore? Does anybody really care?

I'm sitting here, working on a song, using a computer program that takes the place of hundreds of thousands if not millions of dollars spent in mixing consoles, vintage amplifiers, synthesizers, samplers, sequencers, etc. and I'm composing a song I can't play. There's no longer a capital investment barrier to doing what I'm doing, and the skill barrier is getting lower and lower every time I upgrade my software. I'm using virtual musicians that don't exist, but obey my every command. Explain to me how songwriting and recording is a unique skill again?

Now, let's talk about how I learned to use the software. Used to be I'd have to take a few hours a week, haul myself off to some music production school in Chelsea, pay a bunch of money and sit through classes. Now, I'm learning from a subject matter expert through a video series on Lynda.com. I download these videos or stream them to any one of my devices, watch them at my own pace, and take quizzes after I'm done with each section of the course. My progress follows me from device to device, so I can watch them seamlessly whether I'm on the train or in bed at home with my iPad. The quizzes make sure I'm absorbing the material.

So, in learning a software that automates the jobs of a producer, studio engineer and even a couple musicians, I used a learning resource that automates the teacher. Let's let that sink in for a moment.

Over the years, I've been skeptical of automation, especially as it pertains to creative endeavors. Here are some statements I formerly believed in, but don't any longer:

- A computer can't take the place of a musician and won't ever be human-sounding enough to be convincing.

- No digital modeling system will be able to capture the sound of a properly-miked tube amplifier.

- It's more important to writing songs to know how to play than to know the range of possibilities that might make a song sound good.

- Watching pawn shops and CraigsList for people letting go of great-sounding vintage instruments and equipment is worthwhile if you want to capture the unique sounds that equipment can make.

- AI is just incapable of making many of the judgment calls we make as creative people who are capable of writing and performing great songs.

While I'm excited at the possibilities and am looking forward to turning a lot of great song ideas I've had over the years into real songs, I also feel like a career factory guy who just got replaced by a robot.

I took 15 years of classical piano lessons as a kid. I spent countless hours sitting on my bed with a cheap guitar trying to learn how to play songs I liked. I spent the better part of my late teens and twenties trying to scrape up enough money to buy Les Pauls, Fender Strats, synthesizers, stomp boxes, amplifiers, vocal processors and much, much more. I took computer programming classes from the time I was in the third grade all the way up to undergrad. In summation, I've invested a ton of time and money so that I could have a side pursuit of writing and recording music, and automation has made a lot of it irrelevant. It's hard to not be infuriated by the notion that someone could decide to take the Lynda.com course today, get really good at using Logic Pro, and produce something incredible-sounding without having to make any of those investments along the way.

So I've been disrupted. Thankfully, I can adjust. I can get really good at using the software. I can put ideas to songs that (hopefully) no one has thought of before. The possibilities are exciting, but the notion that the barriers of entry have been lowered is scary. Scarier still is that I can see the day when AI composes compelling works and starts to do it better than humans can.

More broadly, it's becoming a lot easier for me to see a lot of creatively-oriented jobs being eliminated - editors, writers, music producers, artists of all stripes.

What happens to our society when the contributions of the people who work in these fields are devalued?