Self-Deception: Pretending The Evil Isn’t Right Under Our Noses

/This is the second in a series of several articles regarding the state of the online marketing industry. Each article in the series deals with the notion of self-deception, the idea that we're kidding ourselves regarding many of the things we think will lead the online marketing industry to success. It is vital to the success of the industry that we examine these instances of self-deception and address them. Three months ago, my grade school chum Craig and his wife Jen purchased a brand-new Compaq PC with their wedding money. I helped them set it up and Jen later subscribed to Verizon Online DSL. Craig and Jen haven’t really owned a computer before, and they planned to use their new machine to surf the web, get e-mail and maybe let their daughter Kayla play some educational games. Jen also uses the Microsoft Office suite for schoolwork and such.

When the PC was only two months old, Jen gave me a call, sounding somewhat frantic on the phone. “Tommy, can you come over and take a look at the computer?†she asked. “I keep getting kicked off MSN and everything’s taking forever to start up.â€

It was a couple weeks before I could get to it, but when I finally did, I was amazed at what I saw. Jen and Craig’s PC was infested with malware to the point at which it was taking over 10 minutes to boot and load Windows. Once it did boot, clicking on almost any application would immediately cause a crash. “Piece of s—t,†Craig muttered under his breath, adding sarcastically “What a great way to use our wedding money.â€

Thorough system scans and repairs using both Ad-Aware and Spybot: Search and Destroy managed to take care of most of the damage. But there were still a couple applications that required a manual registry edit to eradicate, and I simply didn’t have time to take care of it, as I had to go home to help my sister out with some work we were doing around the house. I added a 256MB of RAM to the machine, cleaned it as best I could and went back to my place to help my sister.

After helping my sister out, I was once again asked to take a look at a sick computer. This time, it was my mom’s laptop.

Mom’s laptop was my old laptop. I used it at the office for a while, but then I bought a new machine. It spent some time at the office, being used by an intern before being wiped of most of its application data and given to my Mom to use for e-mail and web surfing.

While our office intern was using the computer, she downloaded a free screensaver. Big mistake. The computer was infected with something that constantly spawned pop-up ads. I later found out that this was yet another piece of malware that could not be uninstalled without a registry edit.

Before I go any further, it’s important that I define “malware.†The meanings of the terms “adware,†“spyware†and “malware†are constantly changing, so it’s important that I define the class of applications that are the culprits in these cases.

Malware (noun) – Any application that generates advertising on an affected machine and also meets one or both of the following criteria:

1) Does not seek explicit permission to serve advertising to the end user. 2) Does not allow the end user to easily uninstall the application

It took two hours of searching Internet message boards for an antidote and manually editing the machine’s registry to get this malware application off my mom’s computer, not to mention the time spent installing Ad-Aware and Spybot and deep scanning the machine.

My mom simply stopped using her last computer for a similar reason. Floods of spam invaded her Inbox until all the time she had hoped to save by communicating via e-mail was taken up with managing and deleting spam. Finally, she just shut the machine off and never used it again.

If you’re the alpha geek among your novice friends, you probably have similar horror stories of your own.

The truth here, staring us right in the face, is that a seedy underbelly of the online advertising industry is ruining the consumer experience for many novice computer users. If it continues, we risk turning consumers away from their computers en masse and crippling the uptake of Internet connectivity (particularly via broadband connections) worldwide.

This is obviously not good for the Internet marketing industry. Ironically, it is the demand for Internet advertising that is driving the proliferation of malware and spam. This, of course, begs the question that many of my colleagues have asked in recent months – “Who the hell advertises with these guys?â€

The answer to this question is simple. We do.

We’re feeding the malware jerks who infect PCs with non-permission-based applications. Our demand for online advertising causes them to exist, and our revenue keeps them alive. Same goes for spam, albeit to a lesser extent, for reasons I’ll share a bit later.

The culprit here is what media professionals call a “blind buy.†Typically, here’s what happens…

A client calls up their advertising agency and tells them they need 10,000 sales leads in the next month, and that they’re willing to pay $100,000 to acquire those leads. The client wants a media plan right away, and the leads must be guaranteed to come in and the client is willing to pay a maximum of only $10 for each lead.

Since the media plan is due right away, a media planner will call one of several “lead generation†vendors or “performance-based advertising companies†to help fulfill the objective. These vendors have something of a standard deal structure that is referred to as a blind buy. The vendor will generate the number of leads requested, but the media planner is not permitted to know where his ads are running. Ostensibly, the media buyer is not allowed to know this because the vendor must protect his business model of brokering ad inventory. If the media planner knew where his ads were running, he could conceivably approach the publishers brokered by the vendor directly, negotiating more favorable pricing. Since the planner has no time in which to do this, the vendor is typically protected from such side deals.

But the real reason the lead generation vendors don’t want the media planner to know where his ads run is that the media planner would be appalled by the venues the lead generation vendor has chosen. Among these venues are spyware and malware applications. This is how otherwise respectful advertisers end up running with malware vendors and subsidizing their unethical practices.

Some lead generation vendors also use spam to generate leads. In this case, the ruse is a bit easier to spot, since lead generation vendors will ask often ask for text advertising to be used in an e-mail. But often, they don’t do so, allowing spammers they work with to write their own copy for spam solicitations that generate sales leads.

In many cases, the ads simply run, the leads are generated and the media planner (hence, the advertising client) never know that their advertising dollars are underwriting malware and spam. Occasionally, a consumer complaint makes its way back to the advertiser, who demands an answer from the agency. The agency calls the lead generation vendors, demanding an answer. Then, one of two things happens:

1) The lead generation vendor attributes the spam or malware activity to a “rogue affiliate†who has since been dropped from the advertising program, or 2) The lead generation vendor disavows any knowledge of the situation and either blames it on another vendor the media planner uses or on a hacker or script kiddie.

This is usually enough to satisfy a client. The vendor assures the agency that it won’t happen again, the agency assures the client, and the program continues. The client is not incentivized to shut the program down, since the leads are rolling in, and the agency and vendor are able to distance themselves from blame by attributing any problems to rogue affiliates or others unaffiliated with the program.

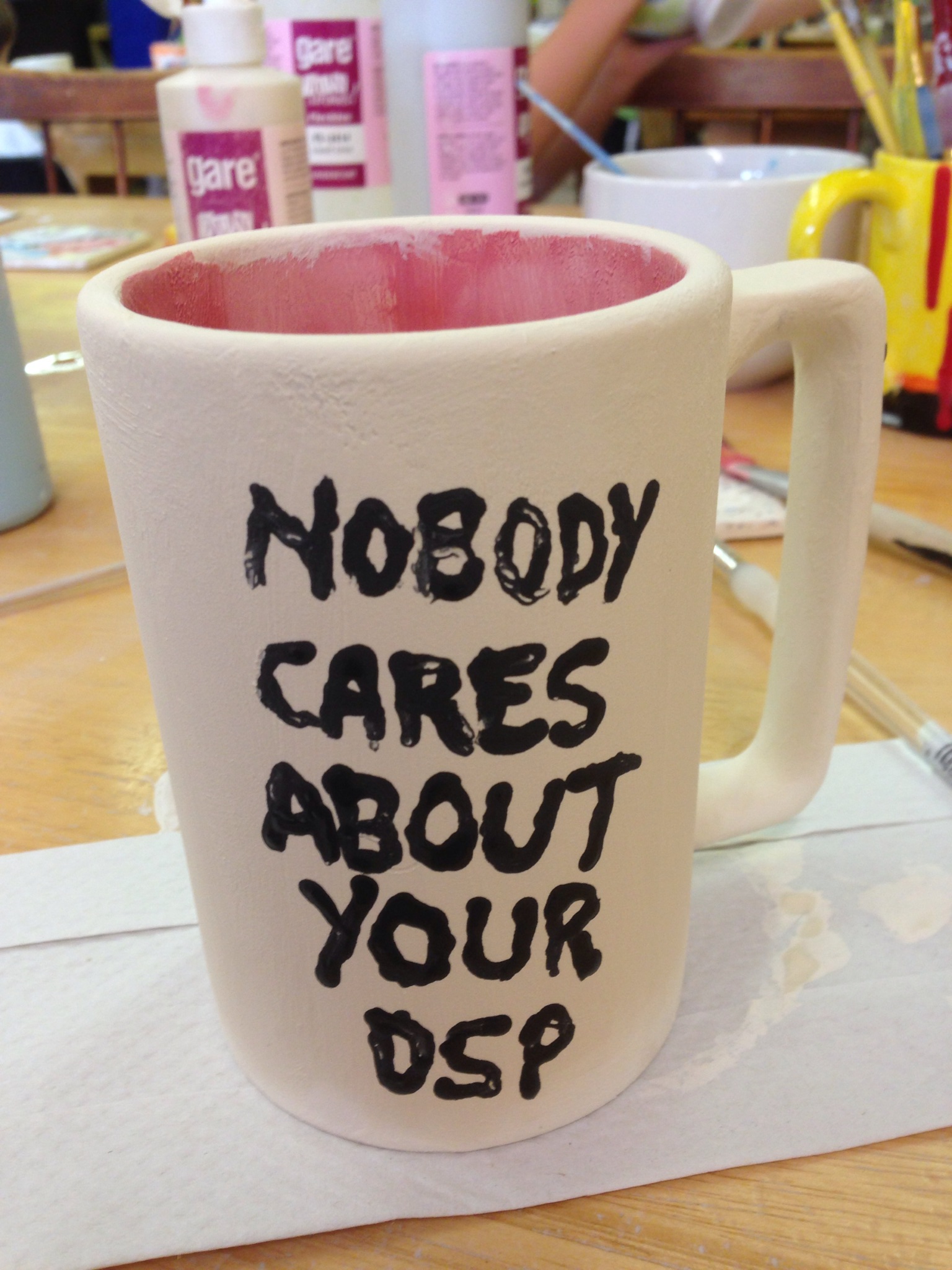

The media buyer in such cases is either ignorant of the ramifications of a blind buy, or he is kidding himself. Entering into a blind buy is tantamount to allowing any Internet entity to provide sales leads, regardless of the format or the venue. The truth is that we are feeding the evil and contributing to the proliferation of malware and spam, all while asking “Who are these people who advertise in spam and adware?â€

As countless computers become overwhelmed with spam and malware, quickly turning into $2,000 doorstops as they become riddled with infections and influxes of bulk e-mail, it’s obvious that malware and spam are killing the goose that lays the golden eggs. We cannot profit from an industry that strangles itself by overriding consumer control to the point at which consumers no longer wish to participate.

So, what do we do about it? I have some suggestions:

- The “blind buy†must be phased out, if not eliminated immediately - While this will cause advertisers much short-term pain as their lead programs take a hit, it simply must be done. Advertisers should know where their ads are running at all times. Clicks, leads or sales that come in from unapproved publishers must be disallowed and advertisers should not pay for them. This will choke off the revenue stream for malware operations and many spammers.

- We need to add language to standard terms and conditions for advertising contracts immediately - The Interactive Advertising Bureau should incorporate the following language (or something similar) into the next version of its standard terms and conditions: “Vendor may not authorize any publisher or ad vendor other than those specified on this insertion order to run client advertising. Neither Client nor Agency are liable for any charges arising from ad activity run with unapproved publishers or vendors.†This will ensure that the agency and client always know where the ads are running, and it keeps vendors from adding random spammers or malware vendors to performance-based buys by removing their revenue stream.

- Ad tracking technology needs to become much better at picking up online ads - Most tools that perform this function are competitive tools that track where advertisers and their competitors are running on the web. But they fail to track much of the activity that runs on smaller sites. If these tools could be adapted to pick up tier three and tier four sites and desktop applications, media planners could spot any unauthorized activity.

- Turnaround times for media plans should be increased - A media planner can turn around a blind buy in less than a day. A CPC or CPL plan negotiated with individual publishers could take several days. When the client calls and needs something yesterday, that request leads buyers to the only source of leads or sales they can turn to in such an abbreviated timeframe – the vendors who provide blind buy opportunities. If agencies had more time to turn around planning requests, it’s a lot less likely they’ll use blind buy tactics.

We’re kidding ourselves by claiming not to know where the revenue comes from that keeps malware vendors and many spammers in business. The evil is right under our noses and unless we wish to continue to fund the onslaught of malevolent applications and bulk e-mail, we should immediately get a handle on where our ad dollars go. If we fail to address this important issue, we run the risk of turning off consumers and slowing or stopping adoption of the Internet channel.